And Mary said, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, for he has looked with favour on the lowliness of his servant. Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed; for the Mighty One has done great things for me, and holy is his name. His mercy is for those who fear him from generation to generation. He has shown strength with his arm; he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts. He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty. He has helped his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy, according to the promise he made to our ancestors, to Abraham and to his descendants forever.” [1]Luke 1:46-55

This passage of scripture is called the Magnificat, because Magnificat is the beginning of the Latin sentence we translate “My soul magnifies the Lord.” It is sung each day in Cathedrals across the land.

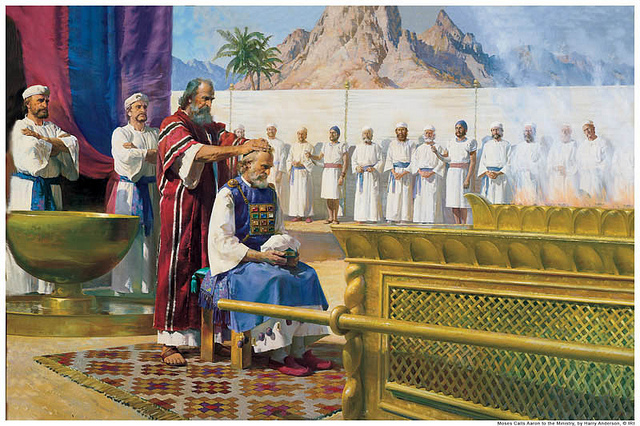

Commentators dispute the origins of this astounding hymn of praise. Almost none of them believe they are the words of Mary herself: suggesting Luke might have gained his inspiration from the Septuagint: the Greek version of the Old Testament he is likely to have known well.

For example, verses from Psalm 22 say:

“the poor shall eat, and be satisfied” and

“to him shall all the proud of the earth bow down.”

But it may also have been a hymn already known to Luke, perhaps written by one of the Jewish religious sects that were around at the time of Jesus. They would also have known the Septuagint well. If that were the case, it would have been adapted for the setting, as it starts off in very personal terms appropriate to Mary:

“he has looked with favour on the lowliness of his servant…

the Mighty One has done great things for me.”

Now I don’t know about you, but I like learning new things, and I can get a bit enthusiastic about sharing them. And there’s a new thing I’ve learnt about the Magnificat that I’d like to share with you. And I perhaps need to warn some of you who, like me, aren’t exactly keen on grammar; that it’s going to be about just that.

The Magnificat is an expression both of how God is, and of how he will be.

I’ve learnt about a thing called a gnomic aorist. Now having studied New Testament Greek, I already knew what an aorist was: it’s a past tense that means something simply happened. It didn’t go on happening. So the plate fell, she made an omelette, the bus arrived. And the word gnomic has nothing to do with garden statuary. If something is gnomic it’s something spoken or written that is short, mysterious, and not easily understood, but often seems wise.

A gnomic aorist describes something that is always true, like a proverb. Birds fly, sugar is sweet. And so, although the verb endings in the original Greek right at the start in the Magnificat indicated by “he has” (he has looked with favour, he has done great things) are the simple aorist; it’s likely that the others: he has put down the mighty, he has filled the hungry- are gnomic aorists. They are statements of What God Is Like – rather than speaking of a single occasion when God gave a drubbing to the rich and powerful, or laid on a good spread.

But there’s also another possible grammatical way to see these words: and that’s as what’s known as the Prophetic Perfect: that they refer to an event that has yet to happen but in faith is seen as having already happened. It’s a bit like the soldiers at the end of D-Day: we’ve won this battle, and so although we’re not yet at VE day, the result of this war is assured.

We know what God has already done, so we know this is what he will do and we can therefore treat it as having already happened. Now I don’t want you to worry: you don’t have to choose between these two possible ways of understanding these words if you don’t have to, in fact I think it’s possible that both interpretations are true at the same time – that the Magnificat is an expression both of how God is, and of how he will be.

The Magnificat was an authentic portrait of Mary’s response to what, in reality was a social disaster.

Certainly that’s an interpretation that’s easy to make when surrounded by hundreds of years of church history in a Cathedral service of evensong. And there’s another both-and I’d like to offer to you about the Magnificat.

When you read the Gospel, the story in Luke is as follows. Mary conceives the child she has been told about and as a result she gives praise. Perhaps Luke’s trying to give us a picture onto the sort of personality he’s seen in Mary. That she was a person so steeped in worship, that this was an authentic portrait of her response to what, in reality was a social disaster. But perhaps he was also giving us another possibility.

Perhaps he’s also saying: the ability to trust God and to praise Him with enthusiasm was a crucial part of her personality, and so maybe that’s one of the reasons why she was chosen to bear the promised messiah.

Give thanks for what God has done, knowing what he can and will do.

Whatever the truth, either interpretation of Mary presents us with an inspiration and a challenge. She inspires us to be a people of joyful praise whatever the circumstances, and she challenges us to be a people who trust that God is just and faithful and good and kind and generous, and who expect Him to act.

So let us, with Mary, give thanks for what God has done, knowing that he can and will do great things.

References

| ↑1 | Luke 1:46-55 |

|---|